From Effortful Decoding to Automatic Word Reading

Bridging the space between “figuring it out” and “just knowing it.”

You’ve taught the decoding strategies. You’ve modeled, scaffolded, practiced, and celebrated accuracy. Your student can sound out words, tap phonemes, and apply patterns… yet reading still feels slow and effortful. If that scenario sounds familiar, you’re not alone. For many students with dyslexia, accurate decoding is only the beginning of the journey. The real bridge lies in helping students move from figuring out words to knowing words—from effortful decoding to automatic word reading.

This post is an extension of Stuck on Decoding? 5 Ways to Scaffold Instruction, where we explored specific decoding supports that help students move through unfamiliar words with accuracy. If you have not read that post yet, I encourage you to start there for a deeper look at the decoding scaffolds themselves and download the FREE PDF with the scaffolds.

Here, we zoom in on what comes next: the instructional moves that help students internalize word reading so those strategies no longer have to be performed aloud or consciously.

Automatic Word Reading

Automatic word reading matters because it frees cognitive energy. When students do not have to devote most of their attention to decoding individual words, they have more mental space for comprehension, vocabulary, and written expression. Research shows that readers build strong mental representations of words through repeated, accurate connections among sounds, spellings, and meanings. For students with dyslexia, this process often requires more intentional instruction, more guided practice, and a carefully planned fading of supports.

Importantly, the gradual release of responsibility is not limited to a single lesson. It is a progression of skills across time. Pearson and Gallagher originally described gradual release as a transfer of cognitive responsibility from teacher to student, and later work by Fisher and Frey emphasizes that this transfer should be slow, intentional, and responsive. In dyslexia intervention, release decisions must be driven by observation, formative assessment, and student response rather than by a predetermined script, and, as highlighted in my book, Teaching Beyond the Diagnosis, instructional time should include an intentional release of scaffolds and supports as students move toward mastery-oriented application.

Rosenshine’s principles of instruction further reinforce the importance of teaching in small steps, maintaining high rates of success, and using guided practice before independence. Together, this body of research aligns with diagnostic–prescriptive teaching: we observe what the student can do, identify breakdowns, and prescribe the next instructional move. To learn more about intentional diagnostic and prescriptive teaching to empower students with dyslexia, you can view this recorded session I did for EdView during Dyslexia Awareness Week.

A Planned Instructional Pathway

When we view gradual release through this lens, moving toward automatic word reading becomes a planned instructional pathway rather than a leap.

Step 1: Begin with Accurate, Supported Decoding

Students must first be able to decode words accurately using appropriate strategies. This includes applying sound-symbol knowledge, syllable and stress patterns, and morphological awareness. At this stage, decoding may be slow and overt. That is expected. The teacher’s role is to model, guide, and correct in the moment so errors do not become habits. Accuracy always precedes speed.

Step 2: Shift from Overt Decoding to Subvocalizing

Once a student can decode a type of word with reasonable consistency, instruction should intentionally shift toward subvocalizing. Subvocalizing is the quiet or internal rehearsal of sounds and word parts. Instead of saying every sound aloud, the student begins to “say the sounds in their head.”

Teachers can model this process explicitly: “Watch my mouth. I’m not saying the sounds out loud, but I’m still thinking them.” Helpful language includes: “Say it quietly as a whisper,” or “Whisper read,” or “Say it quietly in your brain,” or “Think the sounds, then say the word.” Over time, volume expectations fade from full voice to whisper to mouth-only to fully internal.

This step is critical because it maintains accurate phonological processing while increasing efficiency. In addition, as students whisper or subvocalize the word, the teacher actively listens and provides immediate corrective feedback. This can be done even in a small-group setting.

*Response cue: You may wish to initiate a “response cue” for students to read the word aloud. This can be a snap, tap, or verbal cue, such as “What word?” or “Read.” The speed is then determined by the teacher, who can actively respond to students and adjust the pace. (See video clip for example)

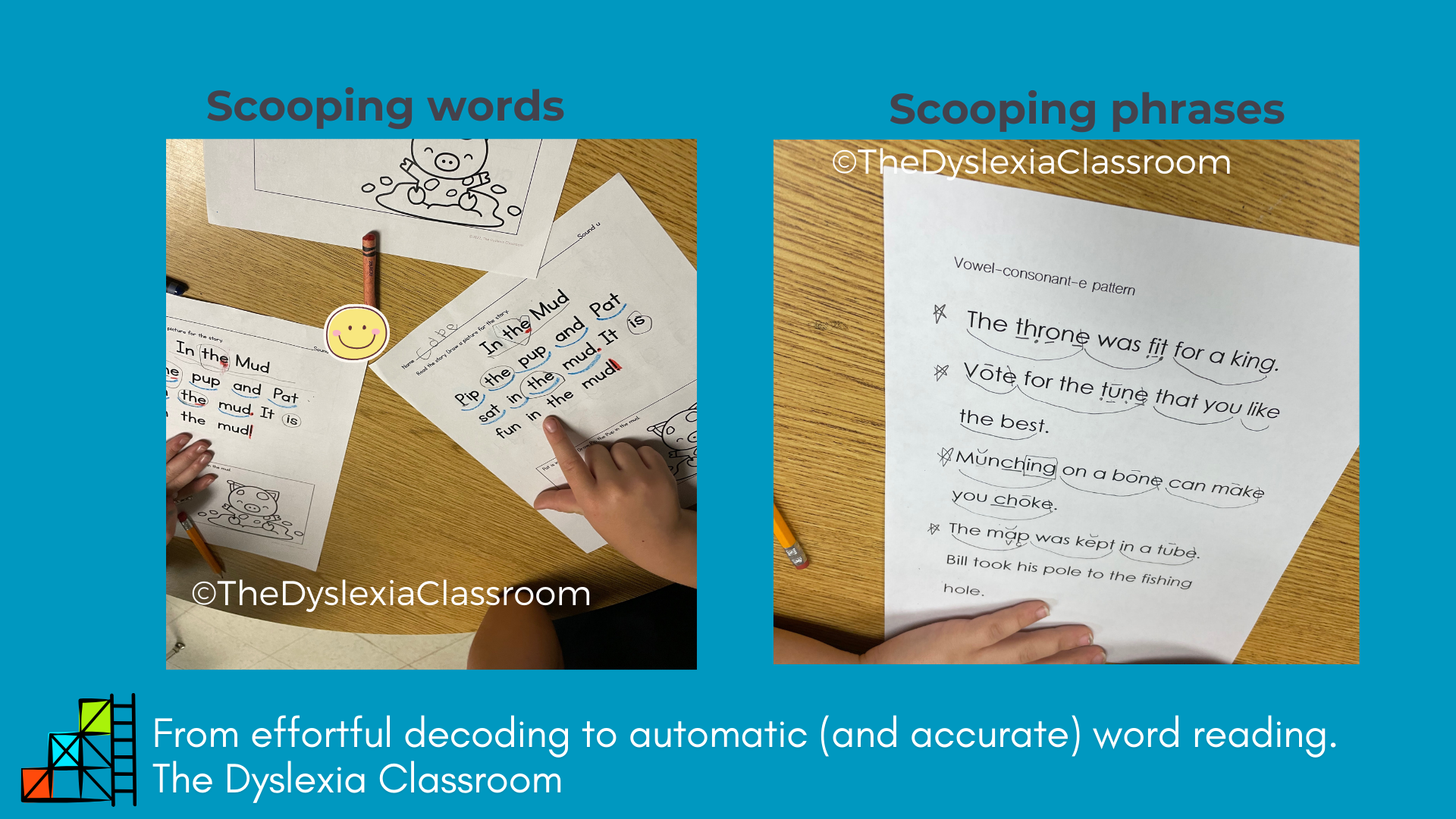

Step 3: Use Scooping to Support Chunking

As students move toward internal processing, scooping becomes a powerful bridge. (Read previous blog posts on scooping.) Scooping is a visual, multi-modal scaffold and the intentional grouping of words to aid in meaning. However, it is important to note that scooping can also be scaffolded, or broken down into small, succinct steps.

For example, students working on building fluency in word-level reading may benefit from scooping groups of letters into meaningful units, such as syllables, base words, prefixes, and suffixes. Instead of perceiving a word as a string of individual letters, students begin to recognize predictable chunks.

Teachers can draw curved scoops under parts and say, “Scoop the parts, then blend the whole word.” Students scoop silently, subvocalize the parts, and then read the word aloud. This supports word reading fluency by reinforcing the idea that words are composed of organized, meaningful structures.

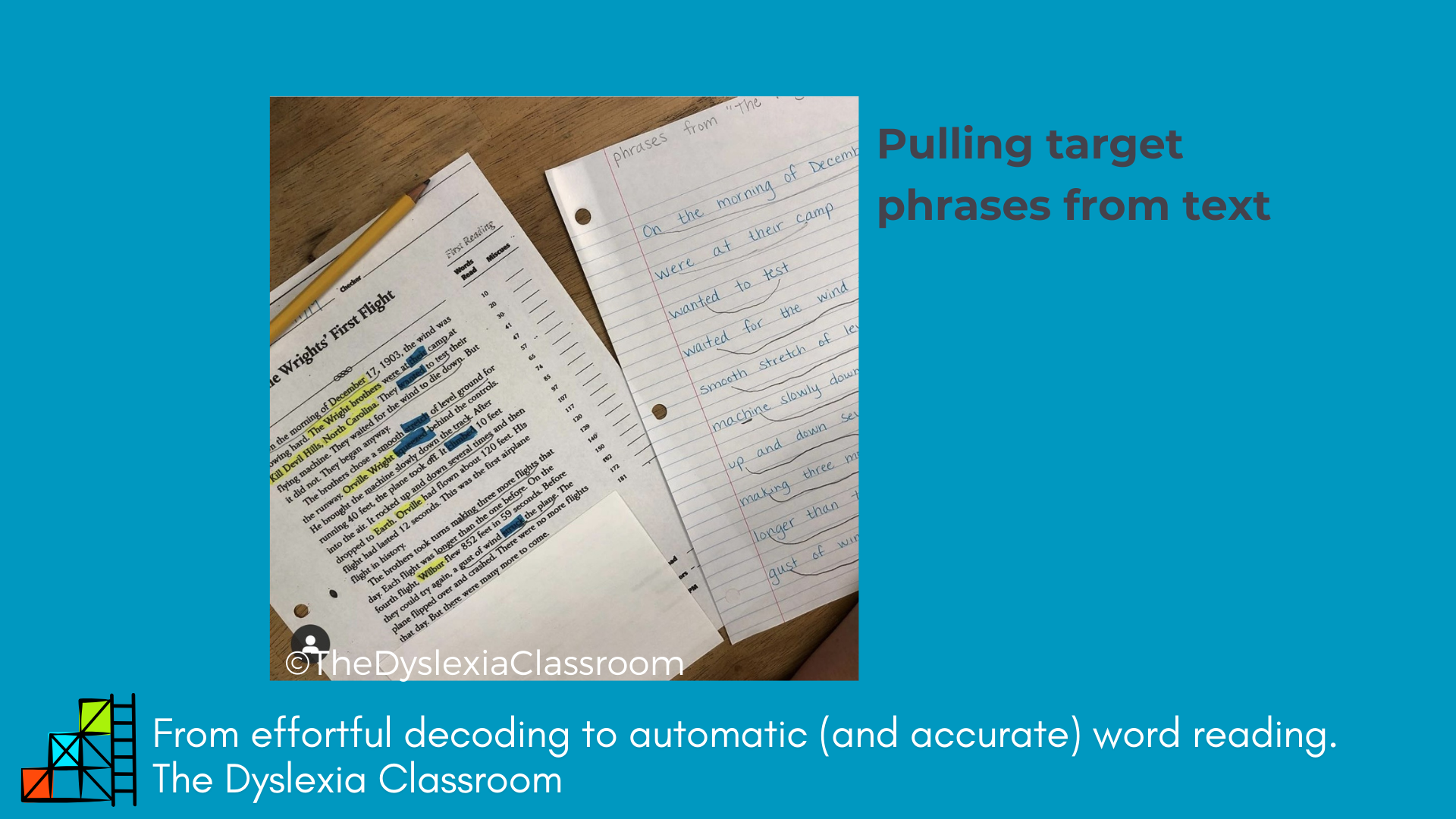

Other students may be moving to the scooping of phrases, in which the instructional focus can be targeted to specific skills. For example, phrases can be directly pulled from a text the student will read, with high-frequency words highlighted. Or, you may determine that syntactic phrases are appropriate for the student, in which you would scoop for who/did what/when. Other times, as students move to text reading, they can scoop phrases as they read, noting pauses within a sentence. This is a powerful strategy that many students with dyslexia will require intentional opportunities for application within and beyond their instructional programming.

Step 4: Build Controlled Automatic Word Reading

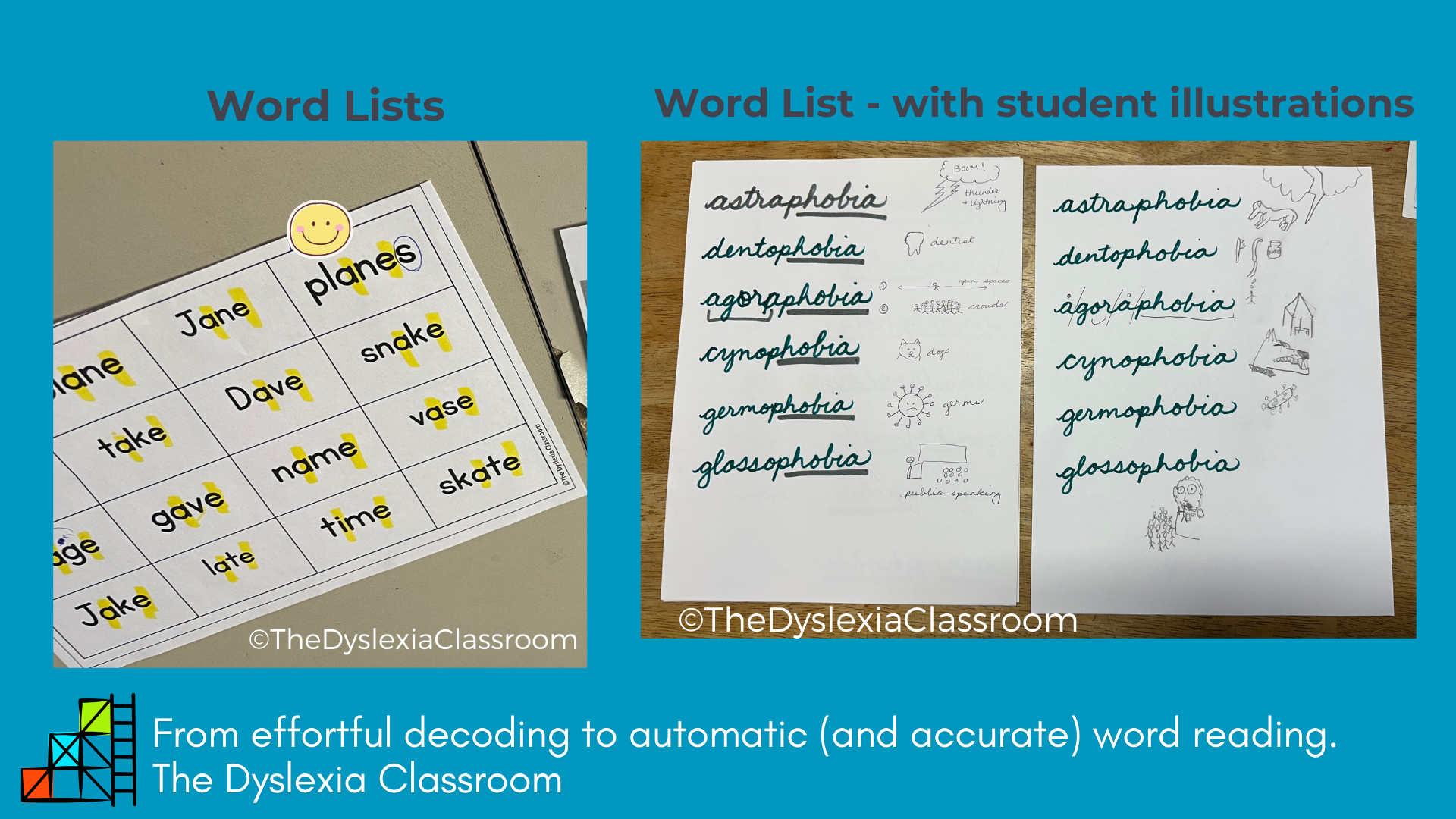

When students can subvocalize and scoop efficiently, instruction should include brief, controlled opportunities to build automaticity with previously taught words. Small sets of words are presented. The student subvocalizes, reads the word aloud, and then smoothly repeats it.

Teacher prompts might include: “Try it again—same word, smoother,” or “Think it, then say it.” The goal is not rapid-fire drills. The goal is accurate, increasingly efficient retrieval. Short daily practice (one to three minutes) is far more effective than long practice blocks. Word lists provide an efficient way to build automatic word reading. (See upcoming post on the importance of intentional word lists within dyslexia intervention)

Step 5: Transfer Word-Level Skills to Sentences

Automatic word reading must extend into connected text. A simple and effective routine is:

The student reads the sentence silently to themselves first, using subvocalizing and scooping as needed. Then the teacher and student choral read the sentence together.

This routine gives students protected processing time while allowing the teacher to model phrasing, expression, and prosody. It also reduces performance pressure and supports successful fluency practice.

*This is an effective strategy to use in all instructional settings (small group and 1-1). Establish a cue for reading chorally, such as a snap/tap/verbal cue. The teacher will closely monitor the students' subvocalizing and reading the sentence, then indicate when to read together. I have my students place their finger back on the first word of the sentence to indicate they are ready.

Step 6: Use Repetition with Purpose

Automaticity grows from meaningful, cumulative repetition. Words and patterns should reappear across days and weeks in different contexts: word lists, sentences, and short passages. Review should always connect to previously taught content and current instruction. Random word lists and disconnected practice rarely produce lasting change.

Helping students move from effortful decoding to automatic word reading is about creating purposeful pathways. We provide scaffolding when students need it. We fade scaffolds when evidence shows readiness. We reteach when breakdowns appear. The science guides what to teach and how skills develop. The art of teaching lies in knowing whenand how to adjust.

Accuracy opens the door.

Efficiency walks students through it.

Automaticity lets them soar.

For modeled examples of subvocalizing, scooping, and sentence routines, be sure to watch the accompanying video.

References

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5–21.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2014). Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility (2nd ed.). ASCD.

Harrison, C. (2025). Teaching beyond the diagnosis: Empowering students with dyslexia through the science of reading. The Dyslexia Classroom.

Harrison, C. (2023). Stuck On Decoding: 5 Ways To Scaffold Instruction. The Dyslexia Classroom Blog.

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2015). Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Wiley.

Moats, L. C. (2020). Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. American Federation of Teachers.

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317–344.

Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 36(1), 12–19, 39.

Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain. HarperCollins.